Historical background

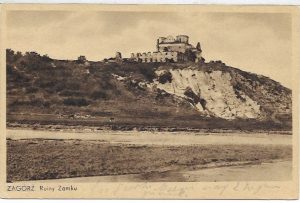

The history of the Carpathian macro-region of Central and Eastern Europe has been shaped by complex cultural, civilisational and political processes. One of the most fundamental and momentous was undoubtedly the Christianisation of this area, integrally connected with the beginnings of the statehood of Poland, Hungary and Kievan Rus’. From the 10th century onwards, Christian identity determined the directions of international activity of Central European political elites for hundreds of years. With the collapse of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the second half of the 18th century, the Carpathian Foothills became an area of domination of the Habsburg Empire. A dramatic attempt to save Polish independence, immediately preceding the period of partition, was the Bar Confederation. This armed, anti-Russian union of Polish nobility, called by many historians the first Polish national uprising, which lasted from 1768 to 1772, was full of important events that took place in the Carpathian borderland. In the initial period of the confederate uprising, the Austrians allowed the insurgent authorities to reside in the city of Prešov, which is now within the territory of Slovakia. There, on 13 October 1770, the act of dethronement of King Stanisław August Poniatowski was announced. Ultimately, the Viennese court opted for a policy on the Polish question which resulted in military intervention and Austria’s participation in two partitions of the Republic. The place of the last regular battle of the Bar Confederation was the fortified monastery of the Discalced Carmelites in Zagórz. On 29 November 1772, an unknown Confederate detachment undertook the defence of the Carmelite seat besieged by Russian troops superior in numbers and armament, commanded by General Ivan Drewicz. As a result of cannon fire by the Russians, a significant part of the monastery buildings was supposed to be consumed by fire. Local lege says that despite their defeat, the defenders managed to evacuate themselves using underground corridors. Did this really happen? Today we know for sure, that after the collapse of the Bar Confederation Zagórz for long, 146 years was under Austrian rule. Until 1918, the Habsburgs effectively suppressed all attempts to rebuild Polish statehood. The policy of the Austrian invaders, who were skilled in stoking social tensions and conflicts, treated the independence aspirations of other nations striving for their own statehood in a very instrumental way. As in the case of Poland, the paths to self-determination and permanent statehood for the Slovaks and Ukrainians were also long and winding. Administrative autonomy, a liberal approach to the use of national languages and association in social organisations all contributed to an idealised perception of Galicia as the Polish lands under Austrian rule. Despite many freedoms not enjoyed by Poles in other partitioned territories, until the end of its existence in 1918 this region was in fact one of the most backward and poorest provinces of the Habsburg Empire. For this reason, the idea of a rail link between the Hungarian part of the monarchy and Galicia was, especially for its Carpathian, inaccessible areas, a true leap forward to civilisation. It happened thanks to the construction of the First Hungarian-Galician Railway, which, among other things, led through the Slate Tunnel to Zagórz (today’s line no. 107) and further through UstrzykiDolne, Krościenko (today’s line no. 108) and in 1874 connected Budapest with the then militarily strategic Przemyśl.

In the early days of the new connection, between 150,000 and 200,000 passengers used it annually. Their number gradually increased to reach nearly 400,000 in 1887! The scale of the impact of railways on the local economic and social environment is perfectly illustrated by the example of Zagórz, which, as mentioned earlier, very quickly transformed from a small, provincial, agricultural settlement into a dynamically developing railway junction. It had great strategic importance during both World War I and World War II. During both of these conflicts, the Carpathian peoples living next to each other had to stand on opposite front lines in hostile alliances. With the establishment of Soviet domination in Central and Eastern Europe from 1945, this part of our continent was sealed behind the so-called „Iron Curtain” for four and a half decades. During this entire period, all social uprisings for freedom and democracy were effectively suppressed by the Communist regimes. At that time, „cross-border cooperation” between the countries of the so-called „people’s democracy” was of a very peculiar nature, which is best illustrated by the example of the former Krosno Voivodeship, which was assigned a „border” partner region during the People’s Republic of Poland, with its capital in Belgorod, only… 1,250 km away from Krosno! The political and economic changes initiated in Poland in 1989 were instrumental in breaking up the entire Soviet bloc. Ukraine (1991) and Slovakia (1993) appeared on the political map of Europe as independent states. A turning point in the contemporary cross-border relations of these countries with Poland, Hungary and Romania was the establishment of the Interregional Union „Carpathian Euroregion” on 14 February 1993. Its genesis and statutory objectives gave rise to the idea of Europe of the Carpathians, into which the project activities described in the following part of this publication are inscribed.